When I was young, I was sacred, beloved and infinite, I was the beginnings of a mighty dream, I was truth, and I was all. Now I map my way to destiny, unafraid and ever-longing for completion of the pattern that spins around my head. And as yet there are no answers, and paths change with every step, and I slow to choose direction and forget to raise my face. Yet beloved, I will continue, I will echo out, forever, I will trace patterns with my fingers, I am the dreamer of the dream…

In the Christian tradition, the belief is that God reveals himself in dreams, although conversely, the dream is also the place of diabolical revelations. So, in this place and in this state, is revealed to me the pattern and the fabric and the influences on my heart, which I may often miss in my more awakened state.

Jung espoused the dream as a mirror for the ego, for dreams can reveal those things which, when conscious, I keep hidden. Dreams can both teach me and guide me to confront these things; they can encourage and assist me to actively play a part in the growth and development of my personality, an ongoing and fluid creation of consciousness. Each day, I become more fully myself.

The room, wherein lies the bed, is the central, pivotal stage for the development of ego and of self. The unconscious seeks to make itself known. Inscribed over the doorway of Jung’s home and on his tomb are the words: ‘Vocatus atque non vocatus, Deus adevit’ –‘Called, or uncalled, God is present.

The bed is a tangible, physical representation of the dream, a place where I, the ego, I, the body and I, the conscious mind go forward to meet the unconscious, wherein lies the mystery and the wisdom of myself. The bed, and the dream, are bridges over which I cross into the unknown. I cross my bridge; I pass, trembling, over fast-moving waters.

When I close my eyes to the light and enter sleep, immersing myself like a swimmer entering warm waters, I let go of my ego, putting my faith in the God within.

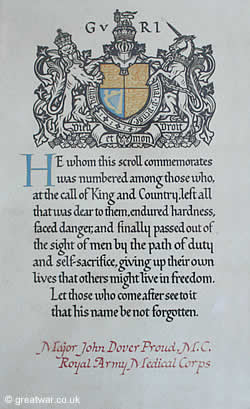

Now I lay me down to sleep/I pray the Lord my soul to keep,

And if I die before I wake/I pray the Lord my soul to take.

Bed space, my heart and my life, distilled down to this moment, this landscape and this me. Centre of my universe, my universe in microcosm, witness to my words and deeds, reflecting my intent, and energy.

When I enter my bed, I am naked in soul and self, stripped away of all pretence, all costume, all position and title. The bed space requires that I am unclothed, and devoid of pride and arrogance. Here, I am myself, I am accepted, and am humbled.

When I go to bed with my love, I embrace the comfort and closeness, or I can vibrate with the absence of it; I tangibly feel the distance and the coolness of the sheets I lie upon.

My children join me here, having once laid here within me. We breathe in unison, as if they had returned to me, under my ribs, safe and conjoined. We are one, living being, dancing to the shared music in our veins.

Now we two, we three, lay within the bed’s embrace, encouraged by its acceptance. We sleep, we nestle, we move to and from each other, we form again and break, we speak of hidden worlds and dreams. I nurse them here, in shadowy silence, the only movement our breathing and our rhythm. I fall asleep over them, lulled by the wash of breath, and life, and peace.

‘A story from your time, Mummy’ a daughter asks, nestling against my curves, creating a groove in the covers and cushions surrounding us, and I begin: ‘Once there was a girl…’, and she and I glance at each other, full of expectation, uncertain of the outcome, though certain of the journey.

I have shared this place with friends and lovers and enemies, I have talked myself inside and out, I have emerged fighting and screaming and have retreated back once more, like an insane wave, falling on a constant shore.

‘It is time for bed’. Who leads who? Who draws the curtains and lights the flame, who sings out the music? The bed receives, the bed responds, the bed becomes the stage for the performance, and the encore.

I lay awake here, hours and days and years, aching with the pain of the loss of self, and love, and direction, my grief absorbed into the depths of my mattress, and my pillow unable to cushion the defeat I feel, but valiantly trying, always trying.

‘Let us say goodbye’ I say, as I lay beside him, once my friend and lover, the father of my daughters, now the stranger he has become to me and to our union.

‘I did not mean for it to be like this’ he says as we both weep, exhausted and desperate.

‘But it is’ I reply, with far more kindness than I will later feel, taking his head and cradling it to my chest, so that we breathe in unison, one last time.

Before I move away forever, I turn to him in a final expression of consolation, and at this moment of separation, when I acknowledge the end, I have perhaps never felt as close to him. I hold him, full of grief and relief, dying another little death, which will be forever etched like acid into my psyche. The bed respects, the bed bows in defeat but still supports me. Goodbye at last to this pretence, this empty, hollowed-out gourd, oh, lay me down to sleep…

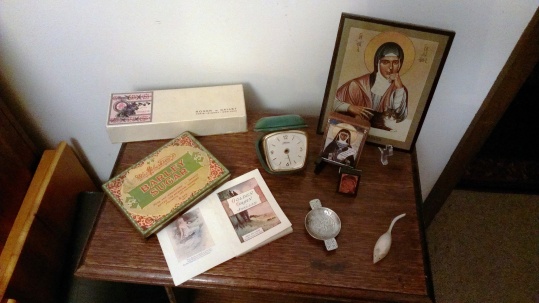

A talisman, and a crystal, too…

And then the bed is reborn, with a new coverlet like the coming of spring. It has a crystal talisman to hang on the bedpost and a new mattress, too, like a galleon fitted out for a new journey into the unknown, into life and sleep, into sickness and health and discovery. I recall the words of John Donne (1630), spoken from the pulpit at St Paul’s over 370 years ago, and heard clearly by my heart today: ‘Our critical day is not the very day of our death, but the whole course of our life’, and I feel myself rise to the challenge of living, once more.

From my bed in my old faraway home, over seven years of summers, autumns, winters and springs I watched the plum tree in my neighbour’s garden rise and fall, discard all semblance of its summer self and strip itself back to its main components – its skeleton of belief and existence, revealing its structure and beauty. So I, in my bed, become myself.

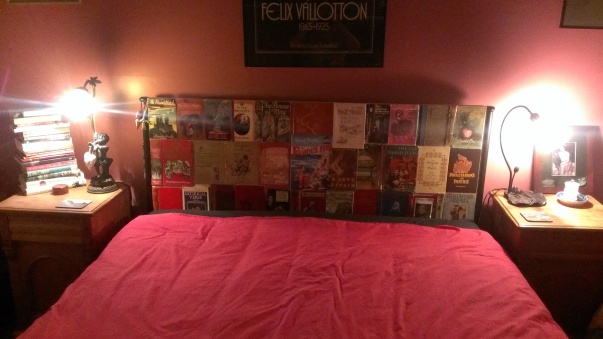

The place where I rest becomes a bridge between my daily life and the unknown, the conscious and the unconscious mind and soul, each evening supporting me on my journey by both giving and receiving me. This place is where I begin my journey each morning and where I return to, faithfully, each night. Where I lie, where I spend my night has become an expression of who I am, and how I am living my life.

My home is a place away from work and from the outside, public world and within it, my bedroom epitomises this private sphere, and is a place where I spend a considerable amount of my life. And I need this space; my bedroom is a significant way in which I construct my identity, in a way that is separate to how others may define me; it acts as a barrier, a demarcation line between myself and others. Here is where I truly begin, where I leave my public self behind to enter my intimate space, filled as it is with my valued and everyday objects.

Here is where I truly begin…

At times I feel marooned here, adrift and absent from safety and security, and at other times I am wholly who and what I believe I am, and my room and my bed then becomes a haven and a place of belonging, and I am secure.

For all the times I’ve moved between and within countries, counties, states and houses, whether caused by my mother’s marriages or her death, or my migration, and my own marriage and divorce, my reuniting with extended family, and with my love, when all around is chaos, I have come to understand that my bed, and my bed space is where I have anchored my girls and myself. It is the centre of our home, and centre to the mysteries of our lives.

This place, this bed is where it all stops: the pretence, the roles I have, the face and image I may present. Here, in my bed, alone, is where I dwell.

This mysterious, island home… John Donne also wrote that ‘No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main’. Yet, living on my island – my home, my room and my bed – I am part of the main, but also distant, and distinct from it.

This is the way it is. This is what it means to be sublimely human.

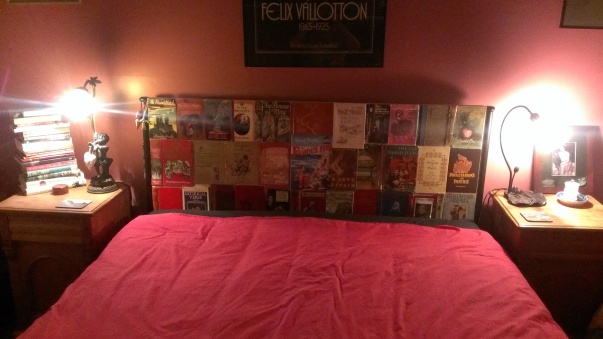

My unique bedhead, made with love

Reference List

Leunig, M (2008), ‘Pillow talk from the dreamtime’, The Age (A2), 5 July, 16.

Scott, R (1997) ed., No Man is an Island: a selection from the prose of John Donne, The Folio Society, London, UK.

The C.G. Jung Institute of San Francisco (2009), website, The C.G. Jung Institute of San Francisco viewed 23 August 2008 <http://www.sfjung.org/Fall2006.pdf> and <http://www.sfjung.org/index.html>